Who was Jean Stevens?

The Search for Jean Stevens Irises in New Zealand

By Anne Lowe, Va.

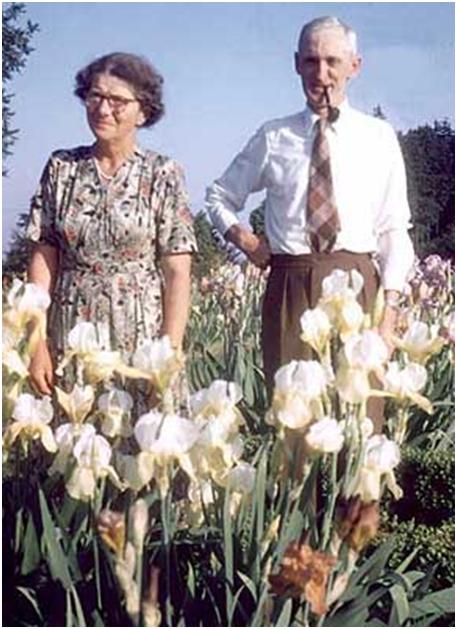

Jean and Wally Stevens, Wanganui, NZ, 1965. Photo by Bob Schreiner.

Last year while I was researching ‘Hybridizers of the 20th Century’ for Tall Talk, I became interested in New Zealand hybridizer Jean Stevens, a.k.a. “the Pinnacle lady”. When Mike and I received an invitation to present a paper at the New Zealand 2000 Symposium in New Zealand, we accepted without hesitation. Here was an opportunity to see the land of Jean Stevens and, through the post-Symposium tours of gardens in both the North and South islands, to see her irises on their home turf. Mike was eager to photograph some of the cultivars we had not seen, and, since the South Island was colder and the bloom was farther behind, and we were going to be in Wanganui, we had high hopes.

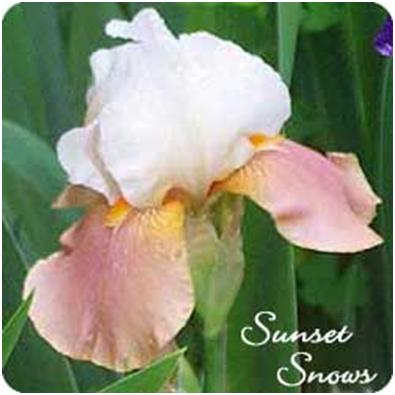

Alas, this was not to be. We saw very few cultivars identified as Steven’s irises since, for the most part, older irises in private gardens are not labeled, possibly because, like us, they don’t know the names. Irises in private plantings are used as a part of the overall landscape (which is usually beautiful) and are rarely found in large numbers. Pinnacle was grown fairly widely but few other varieties were to be found. We were especially looking for Sunset Snows, the iris which has provided a foundation for work done by Dave Niswonger and Barry Blyth in search of the ‘elusive pink amoena’. And we found it — a short, gnarly peachy pink amoena with 2 open blooms! The clump did not look robust, and the garden owner said it was always short and was a slow and poor grower. Mike did his photography thing — that mission accomplished!

We were a bit surprised to find that many local irisarians were not familiar with Jean Stevens, either as a person or as a hybridizer. As with many items of historical interest, those in our own backyard often are virtually unknown. (Mt.Vernon comes to mind for us.)

One gentleman is compiling a list with descriptions of all the Stevens irises. He was unaware that the Stevens Chronicle had already ‘been there, done that”. We have sent him this document which should save him time and trouble — indeed, there may be more than he ever wanted to know.

Since we were the only Symposium segment dealing with bearded irises, our program on ‘Development of Form and Color in Bearded Irises’ gave us a dual platform from which to promote both bearded irises and older cultivars. We laughingly referred to ourselves as “the token bearded people,” all the more accurate since Mike hasn’t shaved in 30 years!

There were so many places and things for us to see and do and our hosts were so generous and gracious, that our New Zealand trek was truly the trip of a lifetime!

The Pinnacle

Pinnacle was introduced in 1949 and was the first yellow amoena.

New Zealander Emily Jean Burgess was born in 1900. She was the daughter of a wholesale florist who, having studied catalogs from the Wallace nursery in England, decided that it was time to start growing irises for New Zealand gardeners. The first large shipment, including the great plants derived from Dominion, arrived in 1921 and were placed in the care of Jean. Hers was the responsibility for writing the catalog and handling customer orders — as well as growing the irises.

Fascinated by these irises, Jean began hybridizing in 1913 and in 1929 flowered what was to become her first introduction. Registered in 1932 and introduced in England two years later, this seedling was appropriately named Destiny. Her connection with Schreiner’s Gardens began in 1936 when Inspiration was seen and purchased by Robert Schreiner. Thus began an association which continued for more than thirty years.

In 1935 Jean Burgess and Walter (Wally) Stevens were married. To them was born a daughter, Jocelyn. Wallywas a nurseryman, an expert plantsman and a collector of rare and spectacular plants including oncocycli and other iris species. The Stevens garden at Wanganui became widely known for its collection of Australian, South African, and New Zealand shrubs.

Beginning in 1939, Jean’s iris were registered under the W. R. Stevens name. Like Cook, Hall and Kleinsorge, Jean Stevens worked a hybridizing line that required vision and tenacity. In her case, it was breeding with the traditional amoena pattern but seeking falls of other colors (yellow, pink, blue). Working with recessives that gave poor germination was a daunting obstacle, but she planned and persevered.

When Magnolia (R. 1939), which was very short on pollen, was crossed to a yellow and white seedling which had no pollen, Pinnacle was the result. Pinnacle was introduced in 1949 and was the first yellow amoena. Regarded by many as the most original color development of the forties, it quickly became popular and was the top AM winner in the US in 1951. Due to the BIS ruling that New Zealand and Australian raised varieties were not eligible for the American Dykes Medal, this color break iris was barred from competition. Had Pinnacle been in the running for the Dykes, can anyone doubt the outcome?

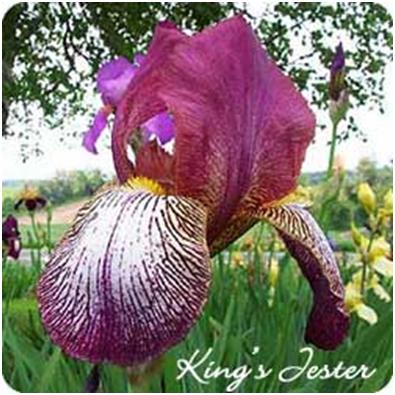

While Pinnacle and Sunset Snows were probably Jean’s finest introductions, one must not overlook some of her other notable irises from the ’40s and 50s: Summit, Dawn Reflection, King’s Jester, Mystic Melody (her personal favorite), Royal Sovereign, Watchfire, Black Belle, Paragon, Moonlight Sonata, Harlequin, Polar Cap and Foaming Seas.

In 1953 Mrs. Stevens received the Foster Memorial Plaque from the BIS and in 1955 she was awarded the AIS Hybridizer’s Medal. Indicative of the respect accorded her in the iris world, she was the principal speaker at the 1956 AIS convention in Los Angeles — the first woman ever so honored. Unfortunately, her health did not allow her to attend the Florence Iris Symposium in 1963 and her paper on iris breeding was read for her.

Following visits to the US in 1956 and 1960, she returned home excited by the potential of Paul Cook’s Progenitor derivatives, little known until then in New Zealand. From Cook’s line she produced numerous seedlings, including Twilight Harmony (1967) with its honey gold standards and gold-rimmed heliotrope falls.

Sunset Snows

Jean Stevens worked toward pink amoenas as diligently as she had worked for Pinnacle. Along the way came Finest Hour, “a red and white amoena” with falls that were plum red. The highly inbred Youthful Charm (1964) became the pod parent of Sunset Snows which was introduced in 1965. This sensational color combination of waxen white standards atop flared and ruffled falls of warm cocoa pink, set off by a red beard, led to three awards at Florence in 1967. Sunset Snows received third place in the Florence trials as well as the Coppa Garden Club di Firenze for original color and the Coppa Piaggio for the best early-flowering variety. How fortunate that these awards came to her while she could enjoy them, for having pursued her interest in irises for more than forty years, Jean Burgess Stevens died suddenly on August 8, 1967.

Of all the irises introduced by Jean Stevens, Sunset Snows has been the most used by other hybridizers. Barry Blyth has relied upon it heavily in breeding his showy bicolors and amoenas. In this country, it has become an important ancestor in the quest for pink amoenas, a field in which many hybridizers are presently working with varied degrees of success. Notable among these are Dave Niswonger, Alan Ensminger and Schreiner’s.

An interesting aside, a Stevens iris named ‘Vanity’ was introduced in NZ in 1950-51 and may still be grown there. However, it never appeared in the AIS Registrations, and so the name was available for Ben Hager — the rest is history.

King’s Jester

The woman who lived high on a hill overlooking the Tasman Sea was endlessly patient with those who really wanted to learn. She authored the well-known book The Iris and its Culture, written especially for growers in the Southern hemisphere. Beginning in 1928, she never refused a request for an article about iris, and was a constant contributor to ins publications throughout the world. Her correspondence was voluminous and her habit of writing late into the night (after working in the garden from dawn to dusk) was well known by those who corresponded with her.

At some point, the gardens at Wanganui were sold and the property is now the site of several large private dwellings which lie behind a wall. As seen from the road, the yards or these homes appears to be well landscaped but it is impossible to tell if any of the exotic shrubs and plants which once graced this site are still ‘in residence’. How sad that there remains so little visible evidence of the indomitable spirit which allowed Jean Stevens to lay the foundation for success in the not-yet-conquered breeding of the ‘elusive pink amoena.

Follow The Links Below For Related Jean Stevens Articles

Follow The Links Below For Related Jean Stevens Articles